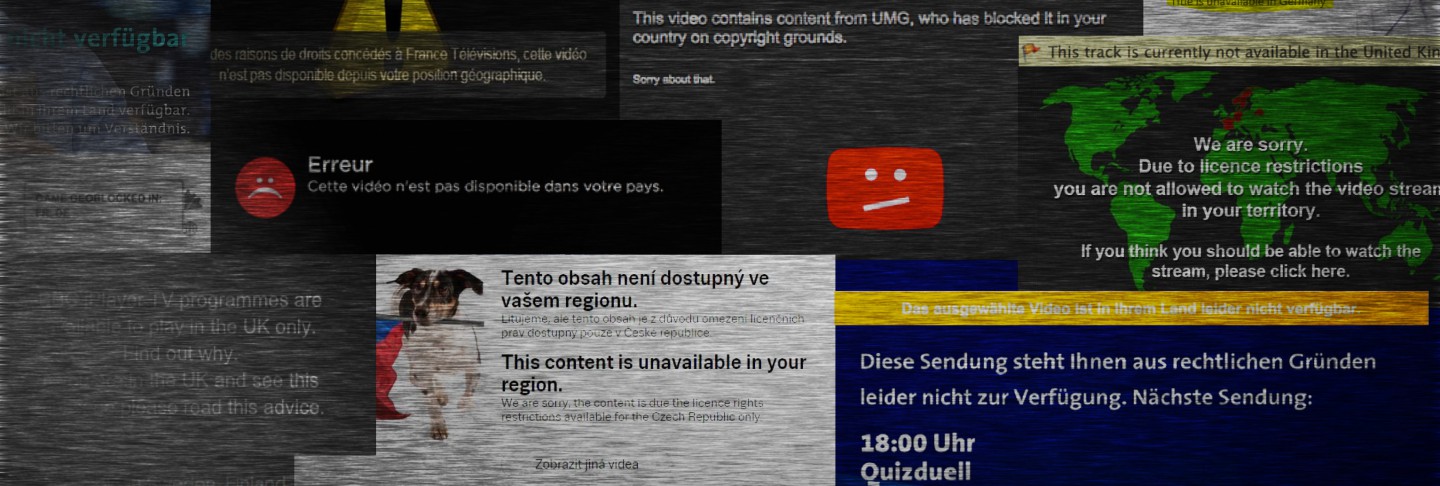

“Geoblocking is essential to protect European cultural diversity”: This was the argument repeatedly put forth in three different European Parliament committees last week.

On the agenda: My copyright evaluation report, in which I argue that we need an update as well as further harmonization of EU copyright rules to meet today’s demand for cross-border cultural access. But MEPs from the big parties and the big member states are taking aim at my proposals, gearing up to reinforce national borders on the Internet.

One MEP offered an analogy: “After all, I can’t buy Finnish bread in any German supermarket or bakery. Far too few people here would buy it, so the market doesn’t offer it to me. And you don’t see me demanding that the European Commission bloody-well make that product available to me!”

I decided to put that claim to the test. See what happened in this 3-minute video:

One tweet and a few hours later I was the fortunate owner of an artisanal loaf of bread from Finland – as it turns out, there is in fact no restrictive territorial bread licensing system in place to keep people abroad from enjoying the products of Finnish bakers.

It appears that politicians aren’t good enough at assessing the level of cross-border interest to base policy on their gut feelings about it. The cultural industry, too, claimed in last year’s EU consultation that there was no unmet demand – while thousands of users reported cross-border access to culture to be a problem in their daily lives.

Yes, Europe is a diverse cultural market with many languages and regional differences. So let’s celebrate that by making this cultural treasure more available, instead of locking it away behind artificial national borders on the Internet. Tweet this!

How does it preserve cultural diversity when Belgians have no way to legally watch cricket? When ethnic minorities in border regions, travelers, migrants, exchange students, etc. are blocked from enjoying cultural works from their region of origin or recommending it to others? When French citizens on the island Réunion (who are assigned IP addresses registered to Africa) can’t access a lot of works from France?

I’m sure these MEPs have the best intentions in mind when they steadfastly defend the status quo. But they must understand:

In the long run, copyright protectionism is not beneficial but dangerous to European culture. Tweet this!

- Copyright protectionism risks capturing European artists inside artificial national borders enforced through geoblocking, denying them global audiences.

- Copyright protectionism risks locking European artists and media companies into obsolete business models that just won’t be sustainable anymore in the information age, removing incentives for adaptation and innovation. An industry whose business models are 100% protected from progress by politics won’t be the one to discover tomorrow’s cultural funding models – models that take advantage of the age of digital plenty, rather than trying to artifically reintroduce scarcity.

- Copyright protectionism risks rendering European innovation in online media services impossible, effectively handing control over the channels of distribution and sharing of media to companies abroad. The attempts to then extract rent from these corporations in the form of new levies and special taxes just adds more barriers to entry for local media startups – just look at the spectacular failures of Spain’s and Germany’s ancillary copyright laws for press publishers.

- Copyright protectionism risks barring Europeans from the emerging practices of transformative creation that open cultural creation up to the broad population and not just those with a profit motive and a publishing contract.

- Copyright protectionism risks making Europe’s rich cultural heritage more and more inaccessible each day by standing in the way of its digitisation, as libraries can’t e-lend books, archives can’t track down rightholders and new copyrights are claimed for digital copies of works that are already in the public domain.

- Copyright protectionism risks setting in stone that in the future, European consumers can only rent media from corporations in digitally locked-down formats, tied to licensing agreements that they have no control over – instead of owning a book or an album like they used to.

- Copyright protectionism risks throwing away the unique opportunity before us for unprecedented access to culture and knowledge for all, including for research and education – in favor of the ultimately lost cause of attempting to artificially enforce, through laws and technological barriers, a scarcity of sequences of bits.

Let’s bring an end to geoblocking

Would you like to pay for access to cultural works but can’t, because online services are not available in your country? Are you blocked from accessing works you have paid for – through subscriptions or taxes – while traveling to another country? Call your member of the European Parliament and ask them to support my copyright report!

To the extent possible under law, the creator has waived all copyright and related or neighboring rights to this work.

There’s some crucial information missing from your post: Was the bread any good? Can Finns actually bake rye using sourdough, instead of into crisp bread?

If yes, will that competition impact Germany’s application with the UNESCO to have its bread culture recognized as immaterial world heritage?

These two articles in Screen International (the main UK-based film industry newspaper), from 5 March and 8 March, show the arguments being made by current players for how the financing model — particularly for smaller films — is squarely based on territorial licensing

http://www.screendaily.com/news/brussels-copyright-plans-meet-resistance/5083935.article

http://www.screendaily.com/news/oettinger-under-fire-over-copyright-proposals/5084043.article

You need to come back with much stronger arguments as to how national broadcasters will still survive and be attractive to distributors even if citizens have digital access to subscription services from elsewhere in Europe; and how it will still be possible (and make economic sense for both sides) for a film to be licensed on a patchwork basis to different locally-tailored broadcasters across Europe, even if anyone from anywhere on the continent can buy into those subscriptions.

Charles River Associates never met an exclusive right they didn’t want to make even more pervasive and even more exclusive; so I don’t give them over-much credibility (“coin operated think-tank”). But to make the case that an end to geoblocking won’t make the sky fall, it would be good to be able to point to a study that has actually done the market research and the modelling, to indicate what the effects are likely to be on small-country broadcasters.

The Netherlands for a long time had clear access to TV from the UK; but this didn’t seem to hurt the vitality of the Dutch TV and film industry.

That’s great Julia and I don’t think that goods should be geolocked. The realities of selling goods inside Europe are a little more complex for small businesses thanks to VAT. From January this year, companies inside the EU selling digital goods to consumers are required to charge VAT at the rate in the customers country and it is a criminal offence to charge VAT to a consumer where none is due. From next year, this will apply to all cross border goods and there is no central repository of VAT rates and regulations across the EU.

This isn’t geolocking, this is VATlocking. It’s a massive disincentive for small business to engage in cross border trade and a mockery of the very idea of a single market. As has already been pointed out, the copyright issues you concentrate on are in many cases actually contractual issues and the EU has no place interfering.

I think Reality (above) makes a valid point. Geoblocking is merely incidental to copyright, it’s the result of a very comprehensive licence fragmentation across countries. Copyright holders intentionally part with their exclusive rights and sell them to national players, often for good money (which can help fund smaller content creators and TV channels). This gives the copyright holders (better) access to foreign consumers; it’s thus a distribution model. Similarly, the BBC restricts access to its iPlayer, because it has granted licences to foreign cable operators who presumably have stipulated exclusiveness within their countries, while the iPlayer itself is funded by British TV licence fees and not paid for by foreigners.

Although I agree that this model is becoming a thing of the past, now that streaming is gaining momentum and consumers have become wary of geoblocks, we should not overlook that there might be a very delicate content market underneath it that could be harmed by a brute-force approach to abolish geoblocking. In that sense the analogy with the bread isn’t all that absurd, Finnish bread is only offered to German customers where there is demand and corresponding supply. Likewise, there is nothing in copyright law that prevents a Finnish filmmaker from offering their films online to German viewers, but it may become a problem when that filmmaker relinquishes their rights to a German company who in turn insists on a geoblock to protect their investment in that deal.