Today, the European Court of Justice significantly curtailed the freedom to hyperlink – one of the basic building blocks of the web. Together with the new special copyright protection for news articles the European Commission is planning to propose next week, the ability of Europeans to point to things online without having to fear breaking a law is in peril.

Could the following message soon be commonplace on the European internet? Read on for details.

1. Links to works with unclear copyright status are risky

In its ruling on the “GS Media” case, the ECJ found that linking to a copyright infringement is itself copyright infringement when done with full knowledge about the work’s copyright status.

Despite correctly recognising that it can be extremely difficult to tell whether a work was posted with the consent of the rightsholders, and that what a link leads to may change over time, the court postulated that “when the posting of hyperlinks is carried out for profit”, such knowledge could be assumed.

In practice, this means that rightholders can sue sites run by commercial entities or that carry ads for any links to infringing content, and can issue takedown notices to individuals, threatening to sue if they do not remove links.

Just when an action is “carried out for profit” is not defined – running a small Google ad or displaying a Flattr button probably already qualifies, and thus obligates site owners to meticulously research the copyright status of everything they link to.

This sets a dangerous precedent and establishes an onerous burden on anyone running a website in Europe. It lends new urgency to what I proposed in my copyright report last year: EU law should clarify that links are never copyright infringement.

Tragically, Commissioner Oettinger is planning to do nothing of the sort, but to instead introduce even more restrictions:

* * *

2. Links to news articles are about to become risky, too

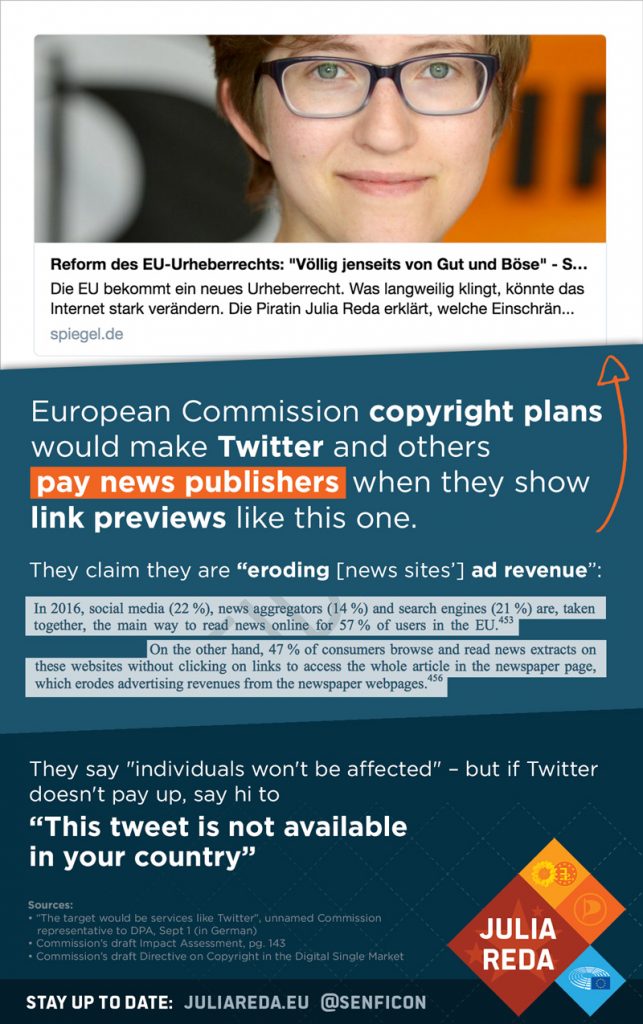

As I first reported two weeks ago, the European Commission’s plans for a new copyright for publishers of news articles would undermine the freedom to link.

Both the Commission and the newspaper industry have since denied these claims in what at first appear to be strong words:

“Nothing we are asking for would affect the way that our readers […] share links on social media […] We are certainly not asking for a links tax” – European Publishers Council, Sept 5

“Private users will still be able to publish […] links to news articles – including short snippets – on their Facebook page or on Twitter without having to pay for it” – Commissioner Oettinger, Sept 5

But if the leaked draft of the law is anything like the final version that will be presented next week, these denials are just word games.

That draft plainly lays out that the publisher of a news article will have exclusive rights to store or copy any part of the article – e.g. the headline or an excerpt of even just a few words – for 20 years. No exception is made for even the tiniest snippets. No exception is made for individuals. Clearly, what we understand today as a link would be directly affected.

A modern link includes a snippet

Since the invention of the World Wide Web, it has been common practice to link to another website using its title or a short quote that explains to readers what to expect at the other end of the link and entices them to click.

Social networks have in recent years made this easier for users by automatically extracting a snippet and an image from a linked site whenever a user posts a plain web address. More often than not, this is what a link looks like on the web today. Here are three examples blended together, all of which are in conflict with the law’s current draft:

Snippets are ads, not theft

Clearly, this is done for the benefit of the linked site, not at its expense. This functionality turns every plain URL into a pretty ad for the content at the other end.

Accordingly, news publishers spend a lot of effort to include special codes on their sites that tell Twitter, Facebook and others just which image, which headline etc. to show when someone links to it.

Thus it is plainly absurd when the industry claims they ought to receive money from social networks and news aggregators for running these ads for their content – that somehow displaying them is an act of theft, that people who see these snippets no longer have an interest in visiting the linked site and thus are depriving them of ad revenue, and that laws must be written to right this horrible wrong.

Yet the EU’s Digital Commissioner Günther Oettinger is letting these lobby demands dictate his copyright reform proposal. Apparently no justification is too flimsy for him to try and prop up established, but declining analogue industries with new fees on digital platforms – with no regard for the massive collateral damage to users and startups in Europe.

It will inevitably backfire

It’s naive to expect internet platforms to give in to this shakedown – they’re much more likely to react by adapting their functionality to comply with the law while avoiding new unjustified costs, which they could do in many ways: Platforms may remove these snippets, make it harder for users to link to news articles, pass the new costs on to their users, start geoblocking hyperlinks or retreat from the European market altogether.

This link is not available in your country.

Tweet this!

So clearly, in practice, this proposal does threaten the ability of Europeans to share links to news online the way they are used to. The denials by Oettinger and the lobbyists either reveal a stunning naiveté – or they are attempts at misdirection by splitting hairs. I won’t let them get away with this and will keep fighting for your freedom to link in the European Parliament.

The press lobbyists already have a plan for when the law will inevitably backfire. A recent tweet gave it away: They’ll point at the measures the internet platforms will have taken to comply with the law and complain that THEY are the ones restricting users’ suddenly all-important freedom to link.

By “users’ freedom to link”, they’ll of course actually mean “platforms’ obligation to pay us”.

* * *

Here’s an infographic on how Oettinger’s copyright law would affect links on Twitter that you can share:

To the extent possible under law, the creator has waived all copyright and related or neighboring rights to this work.

As per my knowledge of copyright law to the court ruled that linking is not does not comply with copyright law can be contrary to the links carry the content that infringes copyright, but in this case need not be a violation if the infringer has no knowledge of copyright issues and work not for profit. The ruling, of course, is issued on the basis of the old rules of copyright. The European Commission should follow the guidelines of the judgment trybunau justice, but there is no obligation because she was the systm copyright and based on this system, the court gave judgment. The European Commission should focus równierz or above all, the judgments of the Court of Human Rights and depart from the principle of “hard law but law” stoswanej in many countries