![]() Today, the European Commission announced its silver-bullet solution to illegal content online: Automated upload filters!

Today, the European Commission announced its silver-bullet solution to illegal content online: Automated upload filters!

It has already been pushing filters to try to prevent copyright infringement – in its communication on ‘tackling illegal content online’, it is going ever further.

The Commission now officially “strongly encourages online platforms to […] step up investment in, and use of, automatic detection technologies”. It wants platforms to make decisions about the legality of content uploaded by users without requiring a court order or even any human intervention at all: “online platforms should also be able to take swift decisions […] without being required to do so on the basis of a court order or administrative decision”.

Installing censorship infrastructure that surveils everything people upload and letting algorithms make judgement calls about what we all can and cannot say online is an attack on our fundamental rights.

But there’s another key question: Does it even work? The Commission claims that where automatic filters have already been implemented voluntarily – like YouTube’s Content ID system – “these practices have shown good results”.

Oh, really? Here are examples of filters getting it horribly wrong, ranging from hilarious to deeply worrying:

cc by-nc-sa liazel

cc by-nc-sa liazel1. The cat that dreamed up a record deal

YouTube’s filters claimed that a 12-second recording of a purring cat contained works copyrighted by EMI Music. Who knew they signed that kind of purrformers!

Lesson: That such a ridiculous error was made after years of investment into filtering technology shows: It’s extremely hard to get this technology right – if it is possible at all.

2. Copyright class is cancelled

A recording of a Harvard Law School lecture on copyright was taken down by YouTube’s copyright filter – because the professor illustrated some points with short extracts of pop songs. Of course, this educational use was perfectly legal. If only the filter had scanned the video for insights on copyright law, rather than just copyrighted soundwaves!

Lesson: Copyright exceptions and limitations are essential to ensure the human rights to freedom of expression and to take part in cultural life. They allow us to quote from works, to create parodies and to use copyrighted works in education. Filters can’t determine whether a use is covered by an exception – undermining our fundamental rights.

3. COPYRIGHT CLAIMS from Mars

NASA’s recording of a Mars landing was identified as copyright infringement – despite the fact that they created it, and as part of the US government, everything the agency creates is in the public domain.

Had camera-shy space aliens filed a takedown request? No, it was a filter’s fault: The agency provided the video to TV stations. Some of these TV stations automatically registered everything that went on air with YouTube’s copyright filtering system – and that caused NASA’s own upload to be suspected of infringing on the TV stations’ rights.

Lesson: Public domain content is at risk by filters designed only with copyrighted content in mind, and where humans are involved at no point in the process.

4. Take it, claim it, delete it

When the animated sitcom Family Guy needed a clip from an old computer game, they just took it from someone’s YouTube channel. Can you already guess what happened next? The original YouTube video was removed after being detected as supposedly infringing on Family Guy‘s copyright.

Lesson: Automatic filters give big business all the power. Individual users are considered guilty until proven innocent: While the takedown is automatic, the recovery of an illegitimate takedown requires a cumbersome fight.

5. Memory holes in the Syrian Archive

Another kind of filter in use on YouTube, and endorsed by the Commission, is designed to remove “extremist material”. It tries to detect suspicious content like ISIS flags in videos. What it also found and removed, however: Tens of thousands of videos documenting atrocities in Syria – in effect, it silenced efforts to expose war crimes.

Lesson: Filters can’t understand the context of a video sufficiently to determine whether it should be deleted.

6. Political speech removed

My colleague Marietje Schaake uploaded footage of a debate on torture in the European Parliament to YouTube – only to have it taken down for supposed violation of their community guidelines, depriving citizens of the ability to watch their elected representatives debate policy. Google later blamed a malfunctioning spam filter.

Lesson: There are no safeguards in place to ensure that even the most obviously benign political speech isn’t caught up in automated filters.

7. marginalised voices drowned out

Some kinds of filters are used not to take down content, but to classify whether it’s acceptable to advertisers and therefore eligible for monetisation, or suitable for minors.

Recently, queer YouTubers found their videos blocked from monetization or hidden in supposedly child-friendly ‘restricted mode’ en masse – suggesting that the filter has somehow arrived at the judgement that LGBT* topics are not worthy of being widely seen.

Lesson: Already marginalised communities may be among the most vulnerable to have their expression filtered away.

8. When filters turn on artists

The musician Miracle of Sound is one of many who’s had his work taken down by filters… on his own behalf. Artists make deals with record labels, record labels make deals with companies that feed filters – and those filters then can’t tell the original artist’s account apart from an infringer’s.

Lesson: Legitimate, licensed uploads regularly get caught in filters.

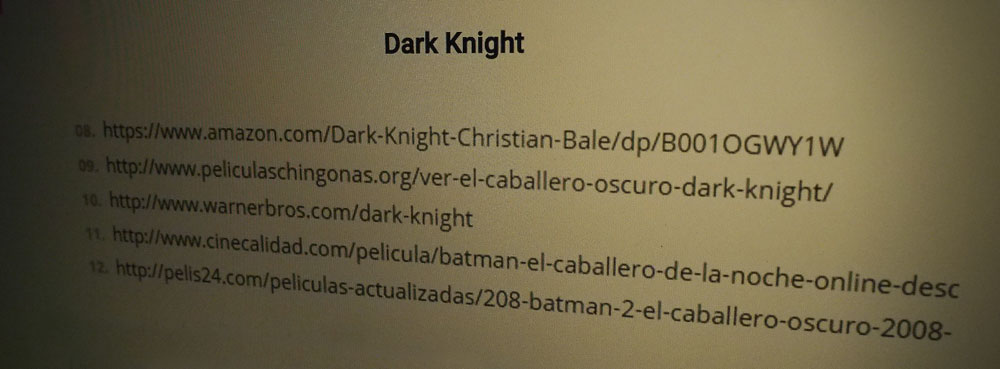

9. The risks of running with filters

Automated systems that send takedown notices are essentially prototypes of filters: They look for infringements like filters, but unlike them, they can’t directly can’t take action. However, the literally millions of complaints they generate are often in turn acted upon by systems that are also automated. Therefore, they fail in similar ways.

In one embarrassing case, Warner Bros. Pictures reported several of its very own websites to Google as copyright infringement, as well as legitimate web stores selling their films. Oops!

Lesson: Not even those wielding the filters have their algorithms under control.

* * *

These cases should serve as warnings to the European Commission and any other overeager lawmakers:

We can’t let automatic filters be the arbiters over content disputes on the internet. Tweet this!

We can’t cut courts of law, due process or even human intervention altogether out of the process without dire consequences for freedom of expression – consequences which we can not accept.

To the extent possible under law, the creator has waived all copyright and related or neighboring rights to this work.

I find your article very clear to understand the situation

You do a good job of reporting what is going on in the EU. Dispite being pro-EU in theory, it does seem to need some improvements in practice before we can take the next step.

And thank you for representing this Dutch pirate in the EU after we failed to get in our own.

Perhaps a ‘quick fix’ to reduce the desire for filters is by valuing taken down content at least equal to infringing content? For instance, if unlicensed contend is valued at €10 per minute per viewer*, why should that NOT apply for taken down content, even if published freely? The publishing can after all be seen as a donation to the public of that €10/minute/viewer.

So if a clip lasts 10 minutes and used to get 100 viewers each day, a 2 week takedown before re-instatement would lead to a fee of 14 days * 100 viewers * 10 minutes * 10 Euro = €140.000,-

Excluding any fines for intentionally false take-downs.

It would encourage those providing the take-down profiles to make sure they have the copyright, and drive down settlement values.

And it would also make it worth the effort to appeal false take-downs.

This idea of equal value could be taken wider to apply to all contracts by binding companies to their own TOS; having to pay demanded fees and penalties for late payments themselves when they take advantage of automated payments comes to mind

* actual value to be an average to be taken from copyright claims made by content holders over the last years

Very good article.